Vitiligo in the young

Vitiligo’s emotional impact

August 10, 2017Vitiligo affects about 0.5% to 2% of the worldwide population. Although vitiligo is not life-threatening the effect of vitiligo can be cosmetically and psychologically devastating, resulting in low self-esteem, poor body image and difficulties in future relationships. Vitiligo commonly begins in childhood or young adulthood, with a peak onset being between 10 and 30 years, but it can develop at any age. However, the mean age of onset of childhood vitiligo in an Indian study was reported as 6.2 years; and 5.6 years and 7.28 years in Korean and Chinese studies, respectively.1

In one Chinese study involving 17,345 inhabitants of six cities they reported a prevalence of 0.56% of the population had vitiligo. In the 0 to 9 year-old age group the prevalence was 0.1% and for ages 10 to 19 years 0.36% They found that 64% of all vitiligo cases occurred prior to the age of 20 years old.2

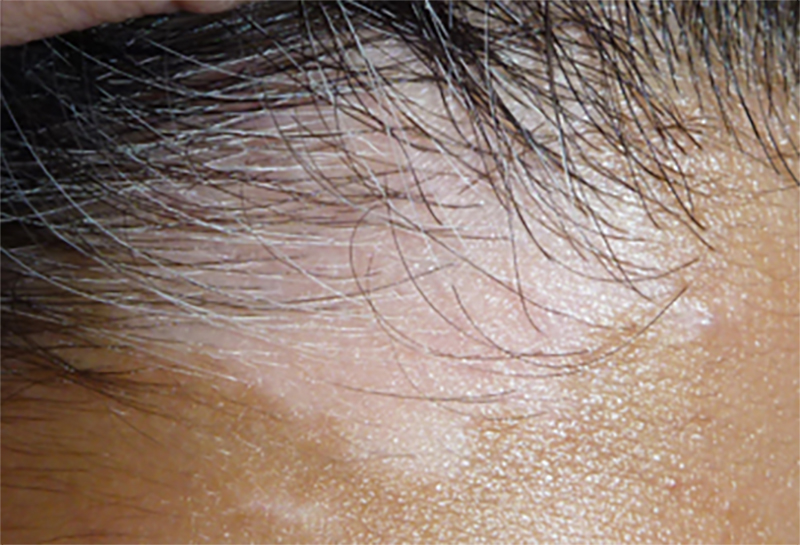

Lesions most commonly begins on the face in children and adolescents (32.6%). There is also a higher prevalence of segmental vitiligo (see our Blog – What is Vitiligo?) seen in children and adolescents (36.4%), compared with adults (11.3%) and the elderly (6.7%). Vitiligo with a stable evolution was seen more frequently in childhood and adolescents (46.2%) than in adults (32.5%) and the elderly (36.7%).3 Infants 4–6 months of age, however, may develop typical vitiligo mainly in the genital or perianal area.4 Approximately 30% of children report signs of itching or burning in their lesions and halo nevi (a freckle surrounded by white skin) is often associated with onset of vitiligo prior to the age of 18 years old.2

Vitiligo can be exacerbated by chemical exposures (this is termed chemical vitiligo or chemical leukoderma, when vitiligo is absent). Although uncommon in childhood, teenagers with vitiligo should be counselled to avoid dying their hair, if possible, due to the risk of exacerbation of disease by chemicals in hair dyes such as para-phenylenediamine or by a combination of contact dermatitis and exacerbation of oxidative damage. When chemicals are involved in the initiation of vitiliginous lesions, lesions will often be found on the scalp and face, and hands and feet.2

Parents of children with vitiligo (8.4%) also report secondary autoimmune disease. The most commonly reported secondary autoimmunity was thyroid disease at 5.4%, although studies assessing subclinical (presence of thyroid antibodies) and clinical thyroid disease suggest the number may be closer to 25%. Thyroid disease is more common in girls with vitiligo and hypothyroidism (slow thyroid release) is six times as common as hyperthyroidism. Rheumatoid arthritis (1.1%), psoriasis (1.1%), and alopecia areata (0.8%) were the three next most common found in a U.S.-based survey. Other reports outside the United States associated childhood vitiligo with celiac disease, Addison’s disease, and pemphigus vulgaris. The presence of alopecia areata and vitiligo overlapping may relate to attack of pigment antigens in the hair follicles causing concurrent vitiligo and alopecia areata.2

Children usually begin to develop signs of anxiety and emotional problems with vitiligo at 5–6 years old, usually when they first attend school. Children may experience ridicule, physical embarrassment, and social isolation, but usually at this age, the actual cosmetic appearance is of more concern to the parents than to the child.4

By 11–12 years of age, the cosmetic disfigurement can become intolerable, and parents should seek some form of counselling for their child so that they can mentally cope with the condition. Children with vitiligo require good support from their family, doctors, medical staff, and the community to accept the disease and to reinforce in the child positive values to help him or her live with the disease.4

It is important to remember that children who are self-conscious may be more susceptible to teasing and bullying. Factors that correlated with being teased or bullied in children with vitiligo included visually apparent lesions with a body surface area greater than 25% and especially where the lesions are on the face for children ages 4 to 16 years old.2

Research has also found that the indirect psychological impact of childhood vitiligo on parents can be equally devastating. The study found that parents, being the closest and the most caring relationships to their affected children, are also victims of vitiligo, and that vitiligo affects their mental state and quality of life to various degrees, and this was more pronounced for the mothers than the fathers. Parents of children with vitiligo were often physically and mentally fatigued, had difficulty sleeping, tended to experience blame emotions and to be very focused on their children’s treatment and care.5 In an Indian study, researchers found that the parents of a child with vitiligo thought about the disease all the time. They felt the disease would pose difficulties in getting the child married and that their child could develop an inferiority complex. Conversely, parental worry weighed on the mind of child; for the child the disease was less of a concern than their parent’s anxiety and unhappiness.6

It is important for parents of young children or teenagers with vitiligo to ensure that they maintain a positive outlook. Often becoming a member of a support group is great way of accessing information, making friends and in general helping to be happy and positive.

Top model, Winnie Harlow, from Toronto, Canada is a great role model, especially for young girls. So, it might be an idea to link into one or all of her sites. She often has little pearls of wisdom

- Website – http://www.officialwinnieharlow.com/portfolio

- Twitter – twitter@winnieharlow

- Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/winnieharlow

- Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/officialwinnieharlow/

Below are links to various support groups: –

For parents and young children

Vitiligo Support International

https://www.vitiligosupport.org/justforkids.cfm

https://www.facebook.com/VitiligoSupportInternational

Sara Madden Books – http://saramaddenbooks.com/books.html – Lucy’s Umbrella – Lucy has vitiligo. She finds beauty in the patterns on her skin. She also finds beauty in the patterns she notices out in nature. Follow Lucy as she goes on a walk through nature, admiring everything she sees.

Support groups for Teenagers

Vitiligo Support and Awareness Foundation – Vitsaf – https://www.facebook.com/VITSAFWestAfrica/?ref=br_rs

Vitiligo Association of Australia https://www.facebook.com/VitiligoAssociationOfAustralia/?ref=br_rs&sw_fnr_id=193875083&fnr_t=0

World Vitiligo Day – 25th June – https://www.facebook.com/WorldVitiligoDay/?ref=br_rs&sw_fnr_id=193875084&fnr_t=0

National Vitiligo Association Inc. https://www.facebook.com/MyNVFI/?ref=br_rs

Closed Membership Groups

Vitiligo – https://www.facebook.com/groups/vitiligogroup/?ref=br_rs with approx.16,000 members

Vitiligo Pride -https://www.facebook.com/groups/14889342050/?ref=br_rs – with approx. 5, 00 members

There are also many more facebook support groups for various countries, just type in vitiligo and search.

Other resources

Vitiligo Project. Org – http://vitiligoproject.org/about/

Vitiligo Awareness – https://www.facebook.com/vitiligoawareness/

Vitiligo Research Foundation – http://vrfoundation.org/

REFERENCES

1. de Barros JC. Et al.; A study of clinical profiles of vitiligo in different ages: an analysis of 669 outpatients.: Int J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;53(7):842-8. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12055. Epub 2013 Oct 18.

2. Silverberg N.B.; Recent advances in childhood vitiligo; Clinics in Dermatology (2014) 32, 524–530

3. Herane M.I.; Vitiligo and Leukoderma in Children; http://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/127256/Herane_MI.pdf?sequence=1

4. Aparna Palit, Arun C Inamadar; Childhood vitiligo; SYMPOSIUM – VITILIGO; IJDVL; Year : 2012; Volume 78, Issue 1, Page : 30-41

5. Amer A.A.A. et al.; Hidden Victims of Childhood Vitiligo: Impact on Parents’ Mental Health and Quality of Life; Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 322–325

6. Pahwa, et al.; Psychosocial impact of vitiligo in Indian patients; Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology, September-October 2013, Vol 79, Issue 5

7. Matin R.; Vitiligo in adults and children; . Clinical Evidence 2011;03:1717